We have all been there. You wake up, stumble into the kitchen, and look forward to that rich, syrupy shot of espresso that kickstarts your day. But lately, you have noticed the pump sounds a bit more strained, or perhaps the coffee tastes a little more bitter than usual. Maybe the steam wand isn’t producing that silky microfoam it once did. An espresso machine is a finely tuned instrument, a marriage of plumbing, electronics, and thermodynamics. When you invest in one, whether it is a modest entry-level model or a prosumer dual-boiler beast, you are making a commitment. To keep that machine pulling world-class shots for a decade or more, maintenance isn’t just a suggestion—it is a necessity.

Maintaining an espresso machine doesn’t have to be a chore that eats up your entire weekend. It is about building small, sustainable habits that prevent the two biggest espresso machine killers: mineral scale and rancid coffee oils. In this guide, we will walk through the daily, weekly, and long-term steps required to ensure your machine remains the centerpiece of your kitchen for years to come.

The Daily Ritual: Small Habits for Big Results

The secret to a long-lasting machine is the work you do in the seconds before and after you pull a shot. Coffee is an organic substance full of oils and solids that, when subjected to high heat and pressure, like to stick to everything they touch. If left alone, these oils turn rancid, creating a sticky, bitter film that ruins the flavor of your next brew and can eventually clog delicate internal valves.

Purging the Group Head

Before you even lock your portafilter into the machine, run a quick 2-second blast of water. This is called a ‘flush.’ It serves two purposes: it stabilizes the temperature of the group head and clears out any stray grounds left over from your last session. After you have pulled your shot and knocked the puck into the bin, run another quick flush. This prevents coffee solids from being sucked back into the three-way solenoid valve, which is one of the most common points of failure in home machines.

The Steam Wand: A Dairy Danger Zone

Milk is the enemy of hygiene if not handled correctly. Every time you froth milk, a small amount is vacuumed back into the wand when you turn the steam off. If you don’t purge the wand immediately after use, that milk sits inside the hot metal tip, cooks, and hardens. Always wipe the exterior of the wand with a damp, dedicated cloth immediately after steaming, and then blast a second of steam into the drip tray to clear the internals. Failure to do this can lead to bacterial growth and a completely blocked steam tip that is a nightmare to clean later.

Weekly Deep Cleaning: Beyond the Surface

Even with perfect daily habits, microscopic particles will begin to accumulate. Once a week, or at least every 20-30 shots, you need to perform what is known as a backflush. This process uses a specialized espresso machine detergent to dissolve the stubborn oils that a water-only flush cannot reach.

Backflushing With Detergent

To backflush, you will need a ‘blind filter’—a solid basket with no holes. Place a small amount of espresso cleaner (like Cafiza or similar) into the basket and lock it in. Run the pump for 10 seconds, let it sit for 10 seconds, and repeat this five times. You will see a soapy, brownish foam exit into the drip tray; that is the gunk you are saving your machine from. Finish by rinsing the portafilter thoroughly and running several cycles with just water to ensure no detergent remains in the system. Your coffee will taste noticeably cleaner and more vibrant immediately afterward.

Soaking the Hardware

While the machine is backflushing, take the time to soak your portafilter baskets and the metal end of the portafilter itself in a bowl of hot water and detergent. Avoid soaking the plastic or wood handles, as the chemicals and heat can degrade them over time. This soak removes the ‘coffee varnish’ that builds up on the brass and stainless steel, ensuring that your espresso only touches clean metal on its way to your cup.

The Battle Against Mineral Buildup

If coffee oils are the enemy of flavor, scale is the enemy of the machine’s life. Scale is the white, chalky mineral deposit left behind when water is heated. In an espresso machine, these minerals (mostly calcium and magnesium) gravitate toward the hottest parts: the heating elements and the narrow copper tubing. Over time, scale acts as an insulator, making your machine work harder to heat the water, and eventually, it will block a pipe entirely, leading to a costly professional repair.

Descaling Your Machine

The frequency of descaling depends entirely on your water hardness. If you live in an area with hard water, you might need to descale every two months. If you use soft or filtered water, you might only need to do it once or twice a year. Using a dedicated descaling solution—usually citric or sulfamic acid-based—you run the mixture through the boiler and the lines. It is vital to follow your manufacturer’s specific instructions, as some dual-boiler machines have specific protocols to ensure the steam boiler is completely drained and rinsed. Never use vinegar; it is not strong enough to remove heavy scale and the smell is notoriously difficult to flush out of the internal gaskets.

Water Quality: The Silent Machine Killer

The best way to maintain your machine is to prevent scale from entering it in the first place. Tap water varies wildly by region. Using a simple charcoal filter (like a Brita) will improve the taste by removing chlorine, but it won’t remove the minerals that cause scale. If you are serious about longevity, consider using an in-tank softening pouch or a dedicated espresso filtration system.

Many enthusiasts have moved toward ‘Third Wave Water’ or mixing their own minerals into distilled water. This allows you to achieve the perfect balance of minerals for flavor (magnesium and calcium) while keeping the alkalinity high enough to prevent corrosion but low enough to prevent scaling. It sounds like mad science, but it is the single most effective way to ensure your machine lasts 20 years instead of five.

Replacing Wear-and-Tear Parts

Just like a car needs new tires and oil filters, an espresso machine has consumable parts that wear out regardless of how clean you keep it. The most common of these is the group head gasket—the rubber ring that creates the seal between the portafilter and the machine. Over time, the heat dries out the rubber, making it brittle. If you notice water leaking from the sides of the portafilter while brewing, it is time for a change. Replacing this every 12 to 18 months is a cheap and easy DIY task.

Similarly, keep an eye on your shower screen (the perforated metal disk where the water comes out). These can become dented or the fine mesh can become clogged. Many owners choose to upgrade to an ‘IMS’ or ‘VST’ precision screen, which features an integrated membrane that is much easier to keep clean and provides better water distribution for a more even extraction.

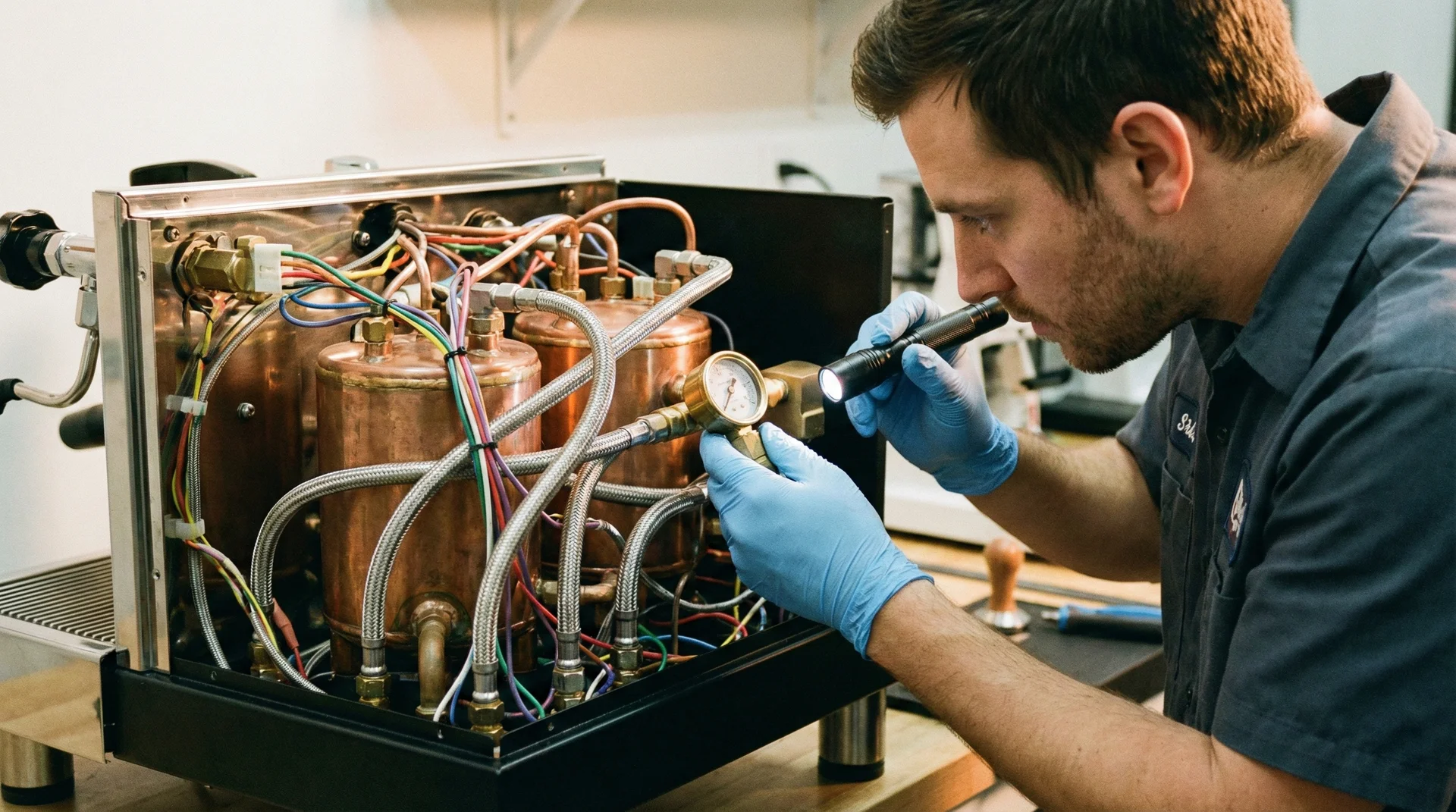

Professional Servicing: When to Call the Pros

Even with the most meticulous home care, some things are best left to the experts. Every 3 to 5 years, it is a good idea to have a professional technician look at your machine. They can check for tiny internal leaks that you might not notice, test the pressure of the expansion valve (OPV), and inspect the electrical connections for any signs of heat damage. Think of it as a comprehensive physical for your most beloved appliance. These technicians have the tools to pressure-test boilers and can catch a small issue before it turns into a catastrophic failure that ruins the logic board or the heating element.

Conclusion: The Reward of Care

At the end of the day, maintaining your espresso machine is about respect for the craft. You have spent money on a machine, and you are likely spending good money on high-quality, specialty coffee beans. By dedicating just a few minutes a week to cleaning and being mindful of the water you put into the tank, you are protecting that investment. More importantly, you are ensuring that every single shot you pull is the best it can possibly be. There is a deep satisfaction in owning a piece of machinery that is ten years old but looks and performs as if it just came out of the box. Happy brewing!